Can we really know our ancestors?

/Almost twelve years ago, a few days after my Dad died, a woman rang my mother and me. She’d seen the death notice in the newspaper (those were the days when you still did such things) and wanted to tell us about the family history she’d help write. I had no idea such a trove of stories and photos existed. So I went on a journey that summer, talking to these new relatives with their old photos and decades-old tales, and meeting another relative up north who had a bound family tree with photocopied photos and first-person stories and letters. I picked this book up again yesterday, as my son had been using some pages from it to practice his crayon artwork (oops). Something struck me about it all. I still found it fascinating, but I also acknowledged that there’s so little we really know about our ancestors, especially in our Western culture.

I know that the first of my Irish ancestors came to New Zealand in 1848, which is pretty early even by our standards. It’s not a done thing to hold all these ancestors in your mind and spirit as you go about your daily life, or even to have memorised their names. In the Maori world, whakapapa is integrally woven into life, and people were taught to recite the generations and generations of their ancestors.

As I read the stories again, I thought about how it’s easy to forget the gut-busting circumstances of 150 to 100 years ago. In this bound book, babies die and this is an accepted part of life, and people spend almost seven months on the ship Ann from Ireland to South Africa to Tasmania to New Zealand, in cramped quarters. The reason these people came to New Zealand is for now dubious circumstances. Concerned about “unrest” between Maori and the British settlers of NZ, Governor Grey called for help from the British army. The people the army would give up were retired and pensioned men in their forties who’d been injured in battle in India and were used to harsh conditions - Robert Edward Kyle was one of those men. For many it was a lucky escape from the potato famine or industrial strife in Britain. The men and their families were called to New Zealand, and they settled in Otahuhu, Auckland. They were only present at one Maori (Ngatipaoa) “attack”, in 1851. They were able to work at whatever jobs they wanted/could get and raise their families, the condition being they had to attend church every Sunday and could be called to fight at any time.

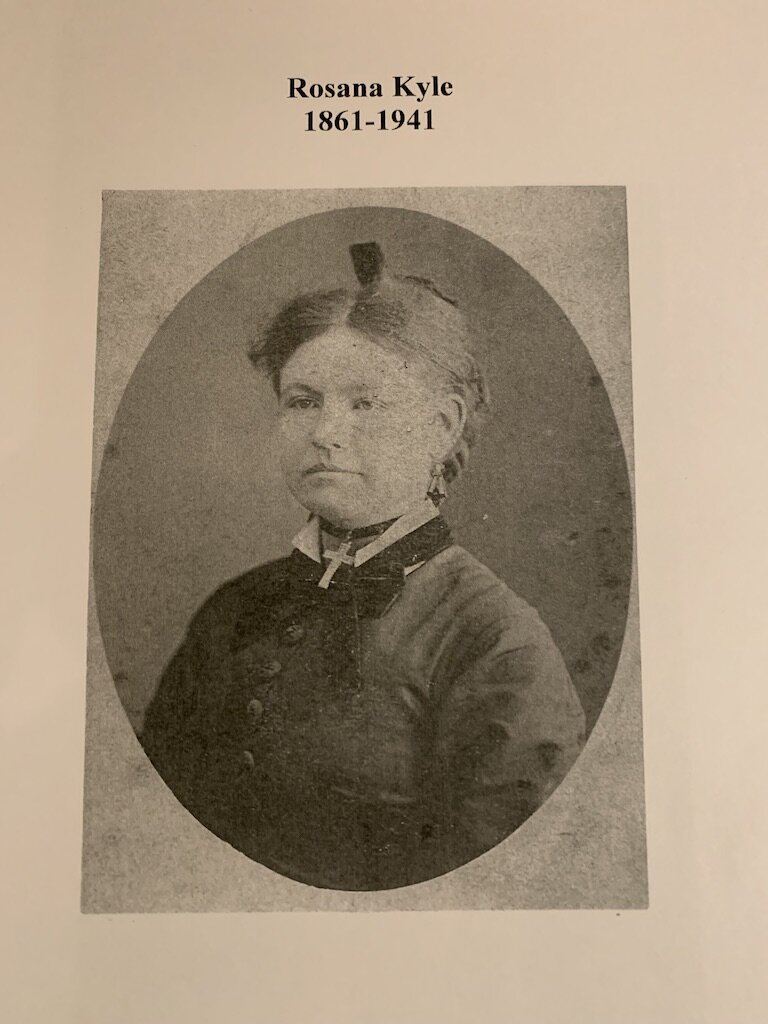

Robert Edward Kyle married a woman twenty years his junior, who he met on the ship. From the sounds of it, he had an arrangement with her father, who was also in the army. Her name was MaryAnn Cobine and they had a brood of 9 children including Rosanna Kyle, who married James Flynn (also from Ireland, though he emigrated later) and is my great-great grandmother.

These people now live on only in the pages of a flimsily bound book, and in the round shape of the Flynn face that has passed down through the generations. But their stories still get lost, and I can never grasp the essence of the person on paper. What were they like? What sort of food did they enjoy, and what booze did they drink, and what personality traits shone in them and what behaviours did they have that were hard to bear? And how did these behaviours trickle down through the generations based on how their own parents were raised – and how did that contribute to the culture we have today? That culture of hardiness, rugby and the way we expect boys and men to behave. That culture of trying to do everything ourselves and of ingenuity.

I wish I’d been able to meet them, but for now the stories and grainy, photocopied photographs are all that lasts.

How do you feel about your family’s history and do you know a little or lots about it?